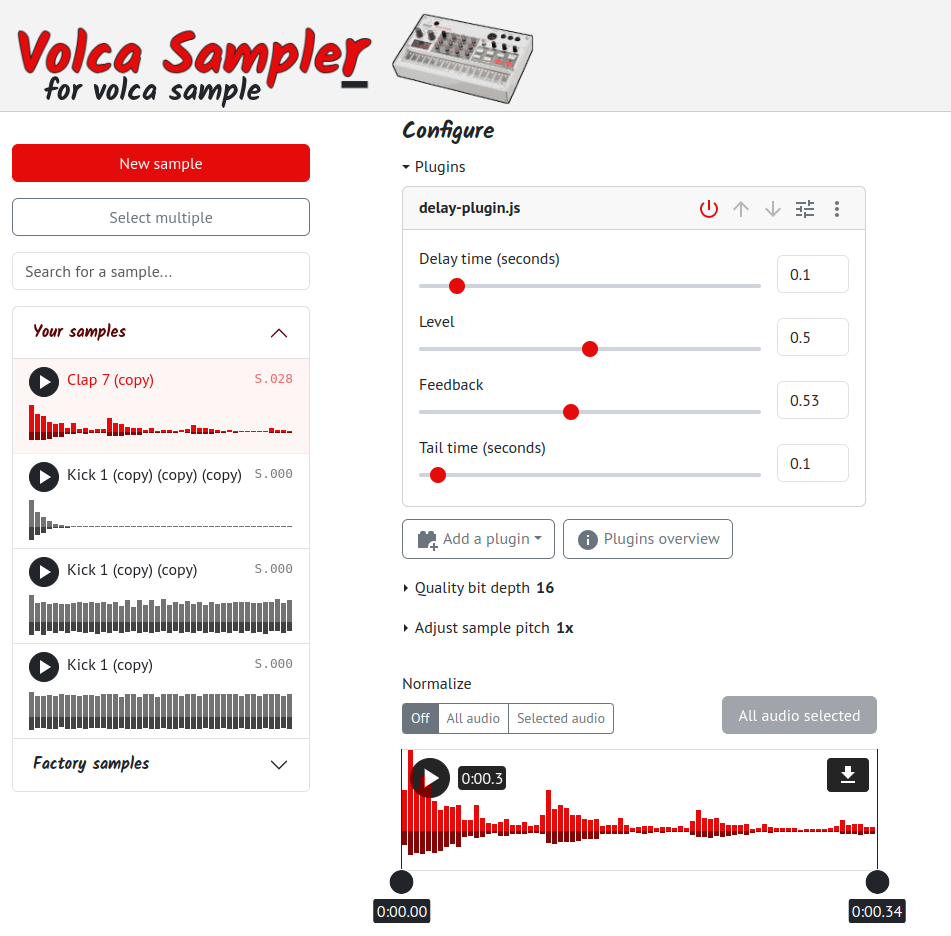

About a month ago I released an app I’d been working on for awhile, Volca Sampler. If you visit the app you might be a bit confused, but among the niche group of folks who own a KORG volca sample hardware sample synthesizer, this app has been very well-received. It embeds KORG’s open-source C library for transferring audio data to the volca sample, making it much easier to load one’s own sounds onto the device.

But to zero in on the subject of this post, after I released the app, I got several feature requests for sample pre-processing options - that is, audio transformations to run before transferring to the device, such as adding silence to the end (to assist with looping), compression, and others. I already offered some options like peak normalization and sample pitching, but I wasn’t sure I wanted to implement every request I got.

So I did what any reasonable dev would do… implement a user code plugin system! 😬

Contraints

The most naive implementation of a plugins system would be one that lets users upload JavaScript that I eval() in the middle of my application code. Volca Sampler has the advantage of storing all of its data locally in the browser, so this actually isn’t the most insane idea. However, it would be a security nightmare if I ever wanted users to be able to confidently share code with one another, or even to prevent users from accidentally bricking their own applications and not being able to access their own data.

So I had to consider what my requirements were:

- Plugins should be able to transform arbitrary audio data.

- Plugins should be able to take advantage of built-in browser JavaScript APIs, most notably the Web Audio API.

- Plugins cannot be allowed to brick the application or unacceptably slow it down.

- Plugins cannot be allowed to disrupt one another.

- Plugins cannot be allowed to delete or modify user data.

- Plugins cannot be allowed to access the network (we don’t want plugins uploading user samples to somebody’s remote server, nor mining bitcoins).

With those constraints in mind, I was ready to do some research.

Prior work

Building a usable and secure plugins system for the web isn’t the simplest task, but there is some prior work. One of the best prior studies is Figma’s, and although I recommend reading their blog post, I can summarize by saying that they eventually chose to run their plugins inside of iframes.

My approach

I ended up deciding iframes were a pretty good fit for me as well. Although I didn’t need my plugins to render anything like Figma plugins do, I did appreciate the security benefits, such as:

- Iframes can be prevented from accessing Local Storage or IndexedDB of the parent context, via sandboxing. This is important for me because I store all user data with IndexedDB.

- Iframes can be prevented from accessing the network, via a

<meta http-equiv="Content-Security-Policy">html tag. - Iframes can run on a separate thread from the parent context and be killed if they run for too long (sometimes… more on that later!).

I also appreciated that iframes:

- Have access to the Web Audio API

- Can exchange messages with the parent, including useful audio data types like

Float32Array

Gotchas

Despite the advantages listed above, I did run into some gotchas:

- Iframes in Chromium-based browsers will share the same thread with their parent, unless they are served from a different domain. Subdomains of the same domain are also on the same thread. So the only way to make iframes not block the main thread is to purchase and serve from a different domain name (in local development this can be simulated by accessing the parent at

localhostand the iframe at127.0.0.1). - Because pages on the same domain use the same thread, plugins loaded in different iframes can block one another, even if they aren’t blocking the parent. The simplest way to handle this is to run only a single plugin at a given time, queueing up subsequent jobs until the prior one has finished. This is potentially slower than running in parallel.

- Creating a new iframe always instantiates a new web context, which can take awhile, and data is copied between parent and child, which can also take awhile.

Possible alternative: Web Workers

One avenue I considered to minimize the issues above was to run plugins inside of Web Workers. Web Workers on their own don’t have all the same security features as iframes, and by default, they have network access and can access IndexedDB - things we don’t want.

However, by running inline Web Workers inside of an iframe, we inherit the iframe’s security features.

Web Workers bring the following benefits:

- Because array buffers can be transferred from main thread to web worker with almost zero cost, the additional data copying latency is minimal.

- Web Workers each run on their own separate thread, so more plugins can run in less time, and they don’t block one another.

- A web worker’s instantiation cost (and killing/re-instantiation cost) is much smaller than an iframe’s, and a single iframe can be used to host many plugins running inside of Web Workers.

The big disadvantage to Web Workers, and the only reason I chose not to use them, is that Web Workers currently can’t use the Web Audio API. This might change in the future.

Conclusions

Overall I’m satisfied with iframes as a vehicle for audio plugins, as they allow user code to securely enhance my application’s capabilities with an acceptable amount of latency.

Performance could be better, and a future where the Web Audio API is made available in Web Workers (or where iframe security features are extended to Web Workers without the need for iframes) could further improve the performance potential for audio plugins on the web.

To learn more about how I implemented Volca Sampler’s plugins system, check out the GitHub repos for Volca Sampler and the plugins development guide.